Sheffield Farms, the Milk Industry and the Public Good

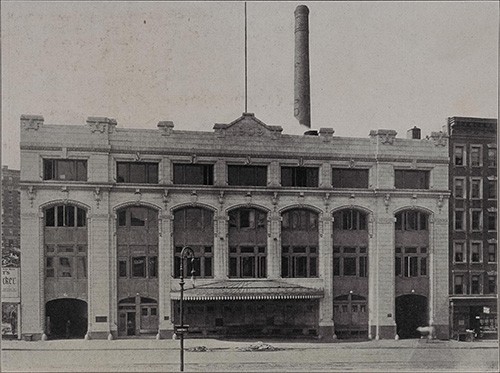

On the south side of West 125th Street stands a four-story, century-old building whose façade is sheathed in milky white terracotta. Members of the Columbia community know it as Prentis Hall, which houses parts of the School of the Arts. But when it was built in 1909, at the same time that the Morningside Heights campus was taking shape a few blocks down Broadway, it was a state-of-the-art bottling plant for Sheffield Farms, one of the many dairy companies that thrived in the industrial neighborhood of Manhattanville.

That slice of history is the focus of an interpretive exhibition, “Sheffield Farms, the Milk Industry, and the Public Good,” created by Columbia University Libraries and University Facilities to explain Manhattanville as a New York nexus, and to fulfill part of Columbia’s commitments to New York City and State in building the Manhattanville campus.

“We really wanted to bring this unique history to life,” said La-Verna Fountain, project sponsor and vice president for Construction Business Services and Communications. “Who better to do that than our very own Carole Ann Fabian? The team that she put together created an exhibit that went far beyond what we could have imagined.”

To get at the heart of the area’s history, Fabian, director of Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, enlisted faculty and administrators from across the University, including historian Eric K. Washington, a Columbia Community Scholar and author of Manhattanville: Old Heart of West Harlem. Historical photographs, artifacts and a short documentary offer a panorama of a diverse rural village as it transitioned to an industrial part of a growing New York. Central to this history are the local children who often fell ill due to tainted milk.

“People who learn about this history will not be able to look in their grocery store the same way again,” said exhibition curator Thai Jones, the Herbert H. Lehman Curator for U.S. History at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Farming was commonplace in Upper Manhattan in the 1800s. Livestock grazed on town greens, so fresh milk was close at hand. As the city expanded north, milk production was pushed further uptown. Cows were housed adjacent to breweries and tanneries that spewed fumes and polluted rivers and streams. Increasingly, farming and industry became intertwined in ways that threatened public health.

“Much of the milk produced for New York was this city milk, which they called swill milk,” said Fabian.

New York’s milk was blue and thin, a product of sickly cows feeding on factory runoff, such as the barley mash from nearby breweries. To give milk a wholesome appearance, producers added chalk to give it a whiter color, and dirt or plaster to add thickness.

Country milk was hauled in on trains, but it was not pure either. Refrigeration was not yet common, so milk would sit on open train cars or in vats in grocery stores, where people ladled it into an open bucket and carried it home.

Not surprisingly, milk-borne diseases led to soaring infant mortality rates. From 1901 to 1905, nearly two in every 10 children died before their first birthday.

“Most people don’t give a moment’s thought to that basic household need. But 100 years ago that decision was a matter of life and death,” said Jones.

To combat this public health emergency, scientists including Columbia chemistry professor Charles F. Chandler joined forces with local leaders and business owners to advance milk science, educate the community and create regulations to make the milk supply safe.

Fabian drew a parallel between the uses of science for the public good then and now, as the University prepares to open the Jerome L. Green Science Center, the first building of the new Manhattanville campus. Where Sheffield Farms once housed its fleet of delivery horses, Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientists will gather with a diversity of scholars in search of new insights on the human brain.

“Our goal at Columbia is serving the public good, using all our capacity to solve real-world problems through our research efforts, our involvement with the community and our advocacy,” said Fabian. “I don’t think any of us knew when we started our research how relevant the Sheffield Farms story was to how we think about our University now.”

For more information, visit the exhibition web page.

This article originally appeared on the Columbia Manhattanville website.

Image Carousel with 6 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

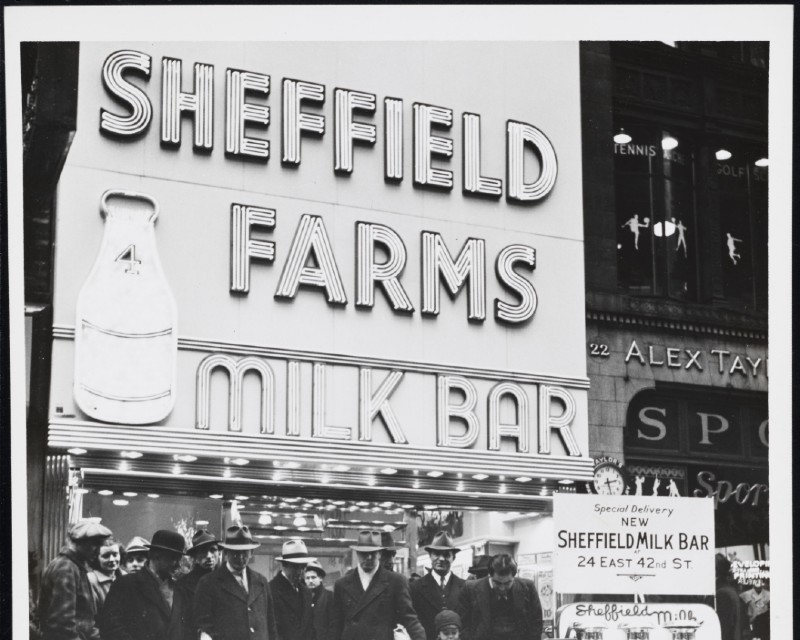

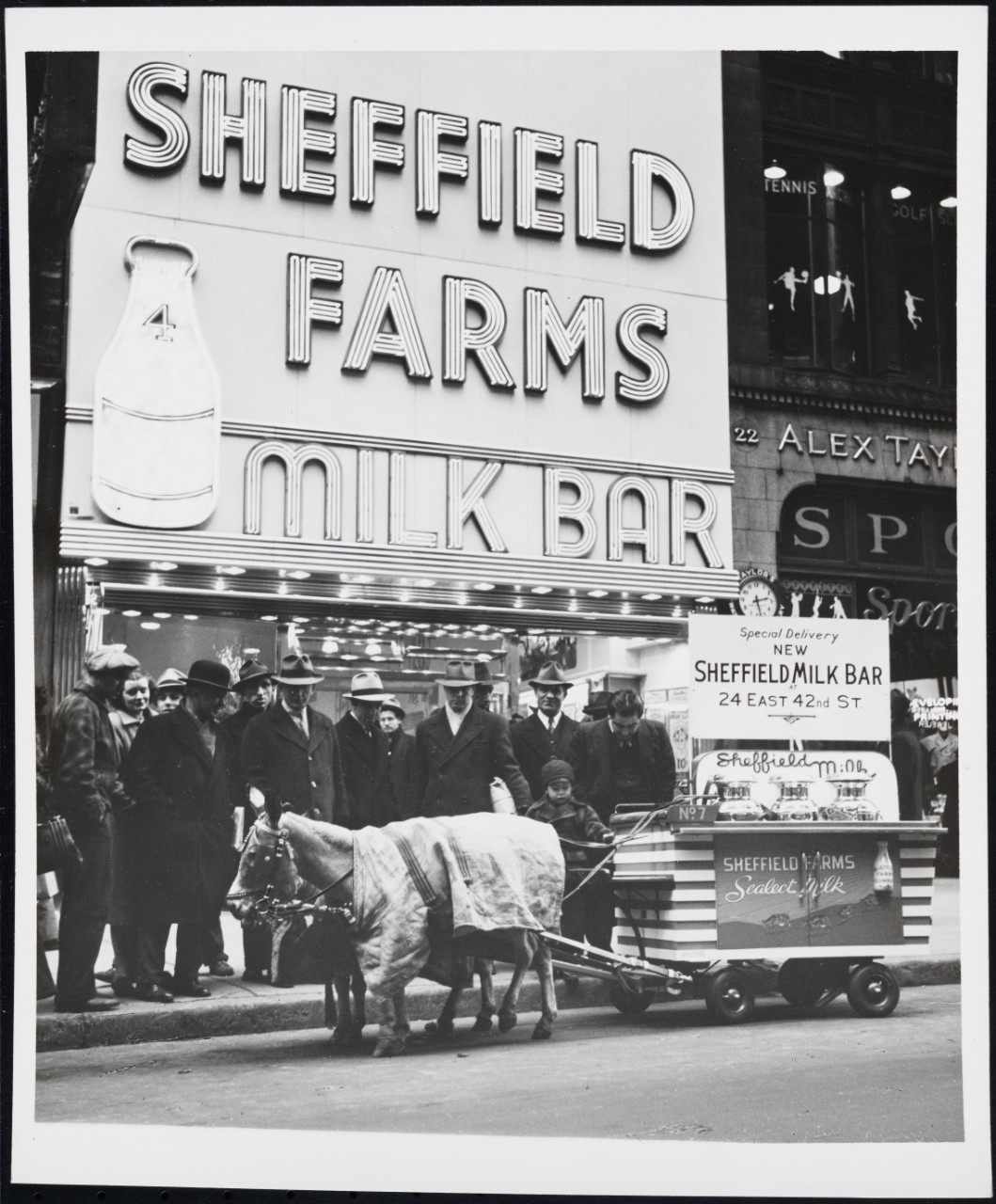

Slide 1: Sheffield Farms Milk Bar, 24 East 42nd Street near Grand Central Terminal, ca. 1940. Photo Courtesy of The Museum of the City of New York

-

Slide 2: “Harlem Mothers Storm Milk Stations,” The Evening World, 1916. Photo Courtesy of Rare Book and Manuscripts Library

-

Slide 3: Children in East Harlem, Union Settlement House, ca. 1940

-

Slide 4: http://news.columbia.edu/newyorkstories2016#/nystories-archive

-

Slide 5: “Sheffield Farms- Slawson-Decker Co., Approved Pasteurization Plant,” Architects' and Builders' Magazine v.43, 1910. Sheffield Farms’ built milk pasteurization, now Columbia University’s Prentis Hall. Courtesy of Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library

-

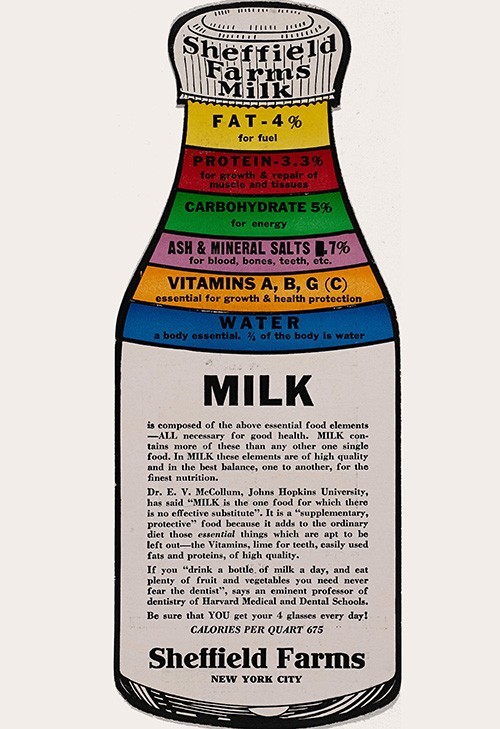

Slide 6: A Sheffield Farms advertisement promoting the benefits of milk

Sheffield Farms Milk Bar, 24 East 42nd Street near Grand Central Terminal, ca. 1940. Photo Courtesy of The Museum of the City of New York

“Harlem Mothers Storm Milk Stations,” The Evening World, 1916. Photo Courtesy of Rare Book and Manuscripts Library

Children in East Harlem, Union Settlement House, ca. 1940

http://news.columbia.edu/newyorkstories2016#/nystories-archive

“Sheffield Farms- Slawson-Decker Co., Approved Pasteurization Plant,” Architects' and Builders' Magazine v.43, 1910. Sheffield Farms’ built milk pasteurization, now Columbia University’s Prentis Hall. Courtesy of Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library

A Sheffield Farms advertisement promoting the benefits of milk