History

Toward Our Future, From Our Past

A century ago, Manhattanville was a bustling port and rail cargo hub that developed into a local center for dairy products, automotive finishing, meatpacking and other light industry. Bounded by the era’s great public works—the elevated subway viaduct on Broadway and the Riverside Drive viaduct above 12th Avenue—the new Manhattanville campus honors that history.

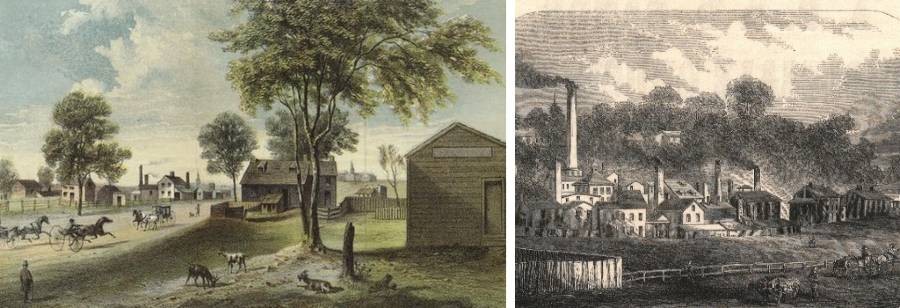

An Incorporated Village

At the western edge of what was then known as New Harlem, Manhattanville became incorporated as a village in 1806. Miles north of what was then New York City’s boundary, lying along the Hudson River between rocky heights, the village soon boasted a commercial waterfront, stables, warehouses, icehouses and factories. A rail station and ferry terminal in the 1800s, followed by the IRT subway station in the early 1900s, helped spur industrial growth. As a result, commerce and transportation converged at a thriving waterfront.

Early Center of Higher Education

In 1853 the Catholic Christian Brothers moved their small school from Canal Street in lower Manhattan to 131st Street and Broadway where they established Manhattan College, which moved north to its current Bronx campus in 1922. Manhattanville College—then a Catholic Academy of the Sacred Heart school for women—had come to what was still an independent village north of New York City in 1847. But, it was located up a hill several blocks to the east on a site that later became City University’s flagship City College campus in an area of Harlem now known as Hamilton Heights.

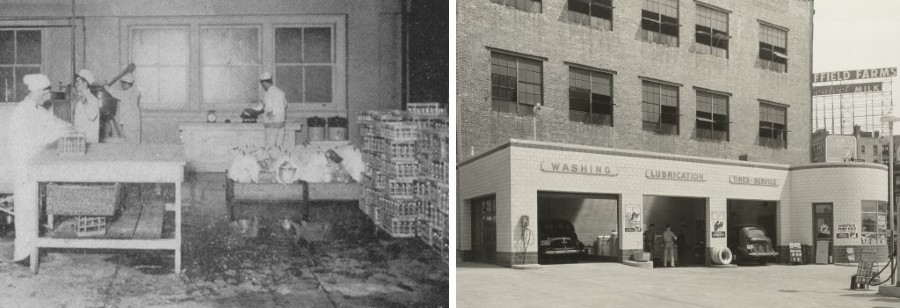

An Industrial Century

In Manhattanville’s western blocks along the river and railroad, dairies and meatpacking industries, including Sheffield Farms (today's Prentis Hall is its former pasteurization and bottling facility) and the McDermott-Bunger Dairy, developed in the late 19th century, delivering healthful “country milk” to a growing city. Curated by Columbia’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library and Rare Book & Manuscript Library, the University has produced an interpretative exhibit "Sheffield Farms, the Milk Industry and the Public Good" that we encourage you to experience in person or online.

Automobile manufacturers established finishing plants in Manhattanville in the 1920s, and the Studebaker and Warren Nash Service Center buildings still stand today. North and south of industrial Manhattanville, development of the IRT Broadway subway—whose iconic 1903 viaduct continues to define the area today—brought waves of residential development to West Harlem. One of many cultural, academic and religious institutions moving north as lower and midtown Manhattan became dense with commercial development, Columbia University began construction of its Morningside Heights campus on the site of the Bloomingdale Asylum, a hospital for the mentally ill, in 1896, and, in the 1920s, established today's Medical Center in Washington Heights.

Changing Fortunes

The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression signaled the end of strong manufacturing growth in Manhattanville. Trucking began to replace water and rail transportation for cargo shipping, leaving the area’s Hudson River waterfront access less of an advantage for commerce. As industries and the jobs they created left the area, Manhattanville lost its promise as one of New York’s manufacturing centers.

As part of widespread urban renewal efforts in the 1950s, New York City built the Manhattanville and Grant public housing projects—alongside the moderate income Morningside Gardens cooperative—on “superblocks” along the east side of Broadway with the hope of both addressing declining conditions in the area and providing a new anchor for a racially and economically diverse community. But one effect of the new developments was to cut off several through streets between Manhattanville and central Harlem, which further isolated the former industrial blocks west of Broadway. In the 1980s and 1990s, there were various proposals by City government to revitalize the area that had largely become characterized by warehouses, garages and parking lots with some remnants of its once-thriving meatpacking and light manufacturing base.

Innovative Plan for Growing Together

Starting in 2003, Columbia began working with leaders in West Harlem to develop a long-term campus plan—a thoughtfully designed, predictable development blueprint that would provide Columbia with much-needed space for new kinds of academic research, while also providing the kind of middle income jobs to New Yorkers that had largely been shed by the decline of private industry in New York and other older cities.

Working with the support and leadership of U.S. Representative Charles Rangel and other elected officials in New York City and state, Columbia engaged in New York City’s rigorous land use review process, known as ULURP, to rezone the project area and adjacent blocks from a Manufacturing zone to a Mixed-Use Special District that would accommodate the construction of academic classroom, research and residential spaces among other uses. In December 2007, the New York City Council voted 35-5 in favor of the proposal.

The University simultaneously worked with New York’s Empire State Development Corporation on a General Project Plan for the site, which earned final approval from the state’s Public Authorities Control Board in May 2009. That month Columbia President Lee C. Bollinger and former president Julio Batista of the West Harlem Local Development Corporation, now the West Harlem Development Corporation (WHDC), signed the West Harlem Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), marking a unique partnership.

Designed to fit within the existing street grid on the blocks along Broadway west to 12th Avenue from the triangle where 125th Street crosses 129th Street north to 133rd Street—and on the east side of Broadway from 131st to 134th Street—the campus plan encompasses more than 17 acres with publicly accessible open space, tree-lined sidewalks and innovative buildings whose very transparency encourages shared knowledge and social engagement.