Schomburg Center Exhibition Explores Community and Creativity Through the Lens of Langston Hughes

The exhibition celebrates Hughes as a collaborator and champion of Black creativity in Harlem and beyond.

Beyond his poignant and poetic stanzas and stories that gave a lens into the expansive Black American experience, a lesser-known but equally important part of Uptown luminary Langston Hughes' legacy was his dedication to advocating for and uplifting the work of Black creatives in Harlem and beyond. Centering the power of community and collaboration, Hughes cultivated a collective of scholars and visionaries who used art in all forms to capture the gravity of cultural, social, and political emergences of their era.

The Ways of Langston Hughes: Griff Davis and Black Artists in the Making, currently on view through July 8 at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, is an ode to the impact of creative connection. Through rare photographs, candid correspondences, books, and a wealth of other archival materials, the exhibition provides a glimpse into the relationships Hughes fostered with the likes of photojournalist Griffith “Griff” J. Davis, poet Margaret Danner, librarian Regina Andrews, and other trailblazers who shaped their respective spaces.

Columbia Neighbors spoke with Novella Ford, associate director of public programs and exhibitions at the Schomburg Center, about Hughes' legacy of mentorship, the importance of amplifying the stories and contributions of unsung pioneers, and modern-day creative movements.

The exhibition centers the power of mentorship. Can you share how Langston Hughes used it as a vessel for community empowerment for Black creatives Uptown?

For Hughes, it wasn’t so much about formal mentorship—though some of that was happening—it was how he would engage other creatives in terms of sharing work opportunities with them, reading and promoting their work, and collaborating. The mentorship may have been more informal than the way we think about the concept of mentorship now. For those who wanted to be in community with him, he was a very giving participant and truly valued their insights and perspectives.

In the exhibition, we have a letter he wrote to Griff Davis about wanting to create a collection of African stories centered on the continent. He entrusted Davis—who at the time was in Liberia—to introduce him to new and young writers who could create this work. This is at a point in Hughes’ career when he was very much somebody in the zeitgeist of what was happening culturally in Black communities. The exhibition features a copy of the collection that eventually comes out called An African Treasury. There’s another letter where Hughes calls on Davis to connect him with a writer who could take on a project for Ebony Magazine.

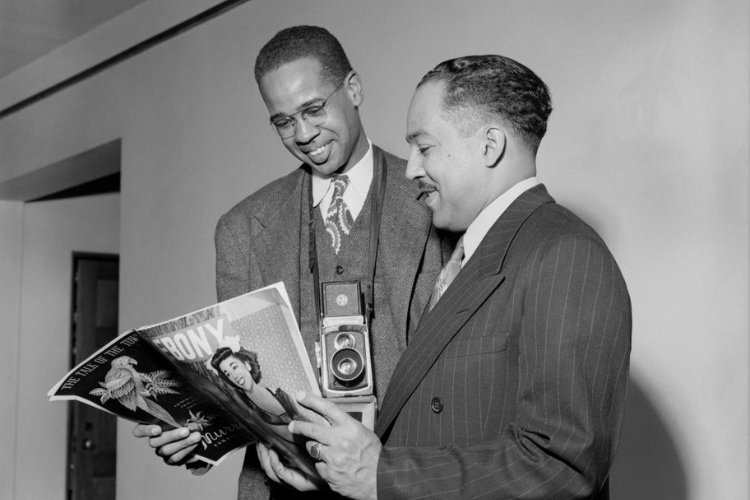

Through these interactions, you’re seeing this form of generosity in not trying to do all of the work himself, but finding ways to put other people on. Hughes truly valued his relationship with Davis and saw him as someone who could connect him to other people and places. Griff Davis is a wonderful guide to understanding what a creative and mutually beneficial relationship could look like.

Griffith Davis is an unsung visionary whose artistry—amongst other creatives—is interwoven into the exhibition. Can you share your thoughts on the importance of bringing his story to the forefront, especially at the Schomburg?

I’ve been learning so much about Griff Davis through the curation of this show and having conversations with his daughter Dorothy Davis who’s also the president of the Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives. Davis is this unsung figure, with an enormous connection to Langston Hughes. Through their relationship we are able to tell a story about Hughes as a collaborator and champion of Black cultural producers across genres and generations.

Through their relationship we are able to tell a story about Hughes as a collaborator and champion of Black cultural producers across genres and generations.

Davis, after graduating from Columbia, became an international photojournalist who’s writing also helped to establish him as an important photographer; covering Africa, Europe and parts of the United States. Subsequently, he was at the forefront of African Americans in diplomatic and foreign services. As the official photographer for the U.S. Delegation to Liberia and Ghana’s Inaugural Independence Day celebration, he’s capturing photographs of places and situations the general public would not see. This is what the Schomburg is all about. Of course, we have known figures in our archives, but it’s also about the unsung folks who helped to fill in the gaps of history—Black history, American history, and global history.

I hope people will research Mr. Davis and go to the website Dorothy has created about his journey. While the Schomburg entered this conversation to talk about Langston Hughes, Griff Davis alone could and should have had his own show.

While attending the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Davis was the only African American student in the Class of 1949. Does the exhibition give any insight into his experiences at the University?

The exhibition primarily focuses on Davis’ photography, but there is a mention of him being the only African American in his class at Columbia. Langston Hughes also attended Columbia but decided not to stay as he faced rampant discrimination when he tried to live on campus.

I posited with Dorothy that given the kind of experience Hughes had at the University, he probably recognized the need for a student like Griff Davis to have some place to go that was not on campus due to his own encounters and experiences. Griff Davis lived at Hughes’ Harlem home on East 127th Street while studying at Columbia and the residence would become a base for Davis as he traveled the world as a freelance journalist.

What are some of the archival pieces from the exhibition that you found the most captivating?

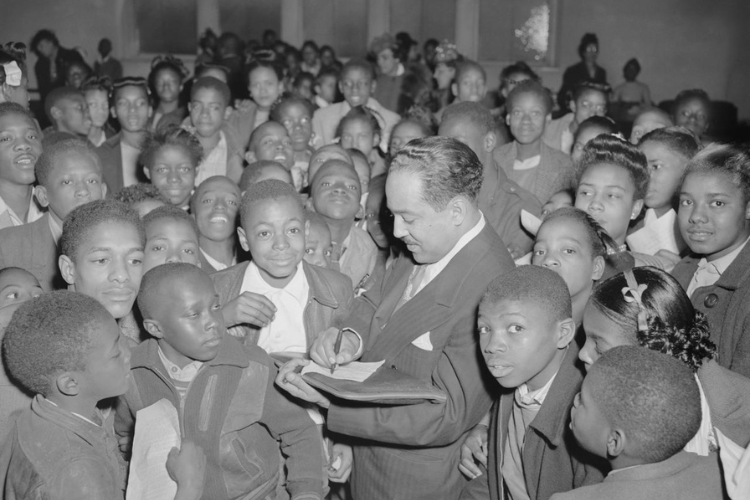

The quotidian photographs of Langston Hughes at his Harlem home and at Atlanta University. He’s in different, multigenerational environments.

In Davis’ archive, there’s a photo of then-vice president Richard Nixon, Martin Luther King Jr., and his wife Coretta Scott King, at a reception in Ghana celebrating the country’s independence. It was the first time Richard Nixon and Martin Luther King Jr. met. The rare photo was held by the State Department and had never been publicly shared until recently because at the time it was captured, at the end of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, they worried about the power of an image. The image speaks to the work Davis was doing in his time.

Even thinking about what’s happening within our world now, there are some definite connections we can make as it relates to what governments and state actors think about the stories they want to tell via photographs and journalism.

Thinking about what’s happening within our world now, there are some definite connections we can make as it relates to what governments and state actors think about the stories they want to tell via photographs and journalism.

We have a beautiful watercolor by Joseph Barker of Langston Hughes's home from our Art & Artifacts Division. We also have photographs from our collection by Roy DeCarava, and images captured on TV sets, and backstage at performances showing Langston Hughes with luminaries like Dizzy Gillespie, Odetta, Harry Belafonte, and many others. There’s a selection of poetry album covers featuring Hughes with jazz musicians and young poets like Margaret Danner. This incredible vinyl collection is from our Moving Image and Recorded Sound Division, where you can listen to these recordings and more! Lastly, there are delightful notes of support from Hughes to figures like Lorraine Hansberry that should be savored when visiting the exhibition.

There are also some really interesting letters that were part of Griff Davis’ archive that are worth reading and provide a lens into this symbiotic relationship between Hughes and Davis. One of the letters highlights how Hughes used Davis and his wife Muriel as inspiration for a collection of stories called Simple Takes a Wife. It’s wonderful to look at the photographs, but the archival material we put on display is also worth reading because there are some really interesting nuggets in there.

Are there any modern-day movements or collectives that have parallels to the creative community that Hughes cultivated?

I’m interested in what it looks like for this generation of writers and other creatives to be in community with one another. What does it look like in terms of being able to support one another and not feel like because I’ve supported you or because I’ve given something to you, it’s going to take away from me?

I think about what Jacqueline Woodson is doing with Baldwin for the Arts. Woodson has institutionalized this opportunity to cultivate Black talent across the board.

I think about the relationships that folks like Jason Reynolds have across communities of writers. He’s a mentor to Candice Iloh, who is now on their third young adult novel. Each winter in December, there’s Harlem Fête, which was started by Woodson, Jason Reynolds, Mitchell S. Jackson, Jennifer Baker, and Yahdon Israel. It’s a way to gather Black writers to toast to the year and help people in publishing connect.

I’ll also mention the Schomburg’s Literary Festival which started six years ago. While we’re still growing it, the goal is for it to really be a homecoming for Black writers across genres. It's something I hope will be a lasting legacy for the Schomburg Center, so in the future somebody will look back and say that was the point at which I learned I wanted to be a writer and I found my community.

What do you want folks to walk away with after experiencing The Ways of Langston Hughes exhibition?

We are a free, public archive. In addition to thinking about Hughes as an important catalyst for Black creativity and development, I hope folks walk away with a deeper understanding of the expansiveness of our archive. I want them to understand what kinds of materials you can find at the Schomburg Center. We use the word "archive" and sometimes people don’t know what it means. We're showing people that it can be your grandma’s letter or a modern-day photo that will mean something to someone in some future, 25 or 30 years from now.

We’re not talking about things that are inaccessible, it might be something you’ll find around your own home. One of the goals I have for exhibitions and public programs is for the general public to find an entryway to history and the archives; understanding what they may have in their own homes might be useful to tell a story about a time, place, space, or person. History is told not just by the names that you know but also by the names of folks you might not know, like Griffith Davis.