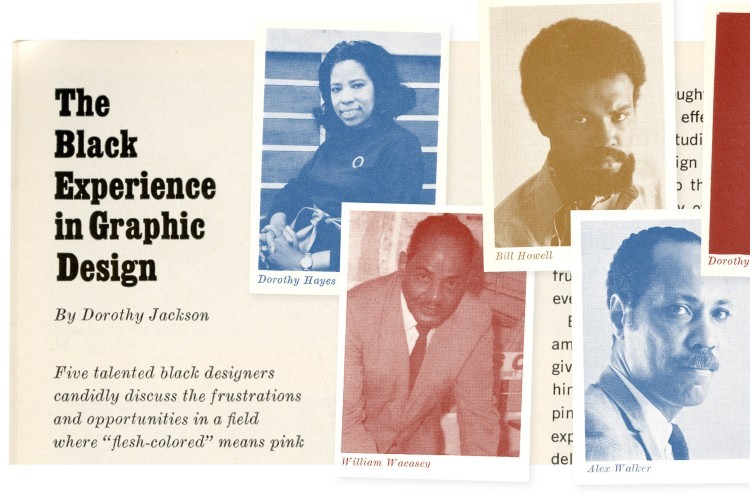

The Black Experience in Graphic Design: 1968 and 2020

This is an excerpt from an article published on Letterform Archive on July 8, 2020.

Michele Y. Washington is a Bundles Scholar.

I’m elated to be amongst a stellar group of designers responding to this article. Some are longtime friends I’ve met along my journey; others are familiar names whose work I’ve followed; and a few are new to me. I’m proud be included with these visionaries.

Reading the article brought to mind a recent interview between author Jason Reynolds and Krista Tippet, host of On Being. Jason shared a proverb from Senegal, “When an elder dies, a library burns down.” For me, this saying resonates with my mission and passion for preserving our history as Black designers in the canons of not just design history, but American history in general.

“When an elder dies, a library burns down.” This Sengalese proverb resonates with my passion for preserving our history as Black designers.

For years, I would hear from young students, “I didn’t know these designers were Black!” Or, students would question whether there were any Black designers who made major contributions to design, as was the case with Tracey Sewell who was told by her professor to not interview me at the Design Educators conference where I was presenting, because “Black designers had not made any major contributions to the field of design”. These interactions sent me on a path of furthering my research, lecturing, and exhibition curation. I’m also working on digitizing my old taped interviews of Black designers, including John Morning, Georg Olden’s conversation at the Art Directors Club, Reynold Ruffins, and Dorothy Hayes, who is featured in this 1968 article. Other taped interviews include Cheryl D. Miller, Sylvia Harris, Tom Wirth talking about Richard Bruce Nugent, and art historian Leslie King-Hammond. One person I interviewed told a story very similar to Bill Howell’s. He said he could get work, but he’d have to go in later in the day and the work would be handed to him so the client would never know he was Black.

Today, the visibility of Black designers is hampered by the lack of attention paid to graduates of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). These designers are often unseen by the profession. They may not be members of the AIGA, and thus not part of their census, and not part of the conversation.

The visibility of Black designers is hampered by the lack of attention paid to graduates of HBCUs.

In considering Black participation it’s also important to remember that attending conferences is costly. This is why the Organization of Black Designers (OBD) was formed in 1990. Their conference, initially organized by David Rice, Fo Wilson, Sylvia Harris, myself, and others, brings together people who work in all areas of design — not just graphic design, but product design, interior design, fashion, and architecture. Harvard’s “Black In Design” conference offers similar opportunities. This networking between disciplines in an environment dedicated to Black designers is an important way for them to be part of a broader professional community.

Before our three pandemics, several art/design schools across the country have begun restructuring their programs across disciplines. Some of these include: Arizona State University, Columbia College, OCAD, and Ramon Tejada at RISD. In 2011, Coco Fusco and Yvonne Watson organized Black Studies in Art and Design Education, calling for Black studies offerings throughout Parsons at The New School. At the conference, Fusco had this to say, which is relevant today with restructuring design programs:

The artists, designers, and scholars we have brought together for this conference share a commitment to finding ways of making Black Studies part of every student’s education. Parsons is uniquely poised to address these matters, due to its location in a university with a longstanding commitment to social justice and in a city with one of the largest urban Black populations in the country.

Right now, I’m privy to several letters sent by black students and faculty from major institutions, all demanding changes. These letters have brought me tears, and made me proud of those who stand up and take a bold stance demanding systemic changes from the top down, to faculty, curriculum, research, and more.

We need to introduce our work to more archives, researchers, and exhibitions.

We need to reexamine professional organizations that, in many ways, are still holding onto the past. We need to offer more ways to mentor our Black and Brown students during school and after they graduate. And we need to introduce our work to more archives, researchers, and exhibitions that travel globally. Examples of this last effort in action:

- The National Museum of African American History and Culture accepts digitized design work.

- Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum established an African American Design Archive about 20 years ago (though I don’t know its current state).

- Jerome Harris curated the “As, Not For” exhibition in 2018 and it continues to travel.

- Mabel Wilson, architect and scholar, has developed archives for MoMA and is one of the organizers of “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America” set for Fall 2020.

- Sekou Jones curated “Close to the Edge; The Birth of Hip Hop Architecture”, held in 2018 at the Center for Architecture in NYC.

- Saki Mafundikwa established the ZIVA Design school in his home country, Zimbabwe. We can surely use his model here in the US.

Read the full article at Letterform Archive.

Michele Y. Washington, New York, NY, has been practicing and researching design for over 30 years, and frequently speaks about the confluence of design and African American history. She holds master’s degrees in Design Criticism (SVA) and Communications Design (Pratt); she teaches Graduate Exhibition and Experience Design at the Fashion Institute of Technology; she is a Columbia University Scholar Fellow; and she serves on the Architecture and Design Advisory Group for the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Michele co-curated “Visual Perceptions: 21 African American Designers Challenge Modern Stereotypes”, and her work was featured in “Design Journeys: You Are Here” and appeared in Women Designers in the USA: 1900–2000”.