The Zip Code Memory Project Provides Connection, Healing, and Plans for Change

The project has become a place for New Yorkers to connect as they process and memorialize their experiences during the COVID pandemic.

Last September, a group of more than 30 Columbians and community members gathered in the garden of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in Morningside Heights to figure out how to grieve and memorialize the losses of the previous 18 months. Over the following months, they would work together creating art, writing poetry, building relationships, and learning to express their experiences as New Yorkers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Zip Code Memory Project was inspired in part by the significance of zip codes in how New Yorkers tracked the progression of the pandemic, as well as the startling variations in transmission, death, and vaccination rates between zip codes.

“The differences were so stark even between 10027 and even a few zip codes into Harlem and Washington Heights. The inequalities that structure our life in the city were so clear,” said Marianne Hirsch, co-director of the Zip Code Memory Project and William Peterfield Trent Professor Emerita of English and Comparative Literature and of Sexuality and Gender Studies at Columbia University.

Tackling the Lingering Trauma of COVID

Hirsch, alongside Diana Taylor, Susan Meiselas, Lorie Novak, and Laura Wexler, a group of academics, artists, and organizers, pooled their experiences exploring questions of memory, trauma, violence, and pain and turned them toward their own communities in New York City. With partners at Columbia and across the neighborhood and community, they sought to tackle the lingering effects of the pandemic and figure out how to heal and how to address the inequities that led to such disastrous outcomes for New York City.

“We brought to our own neighborhood our concern with social inequality and social justice. How can you emerge from something like this, that caused incredible loss, and build community from it?” Hirsch said when speaking with Columbia Neighbors. “The thinking was, let's try to create a space where people can process what happened to them through art based workshops that built trust and allowed participants to create something together.”

Dr. Marilú Maria D. Galván, a Zip Code Memory Project participant, and the Executive Director of Centro Civico Cultural Dominicano, which partnered with the project, spoke passionately about the pain and trauma in her community during the pandemic:

“Many people of our community were affected and devastated. They could not go to the hospital because they were told to stay home. Nobody was around to give them any services. They were infecting each other and dying.”

She was immediately called to document those experiences, helping people share the impact that the pandemic had on them and calling attention to the deep devastation felt by marginalized and underserved communities in New York City.

Like many things in the summer of 2021, the Zip Code Memory Project was conceived as a post-pandemic endeavor, but wound up being a project of the ongoing pandemic. “We thought by the fall of 2021 we would need space to process and rebuild and regain resilience,” Hirsch said. “Everything was still affected or determined by the course of the virus.”

While the project’s location at St. John the Divine allowed for outdoor meetings in the Cathedral’s extensive gardens and use of their large indoor spaces, the project was unable to fulfill their plans to hold meetings in community centers. The Omicron surge in January and February 2022 forced a shift to online meetings, and organizers saw attendance decline as participants got sick, or traveled to care for ill family members.

Community Is Essential to Collective Processing and Memory

Despite the challenges brought on by the new variants and the continued effect of COVID on day-to-day life, the project allowed participants and organizers to connect with a broad range of people and share their experiences.

“I met a nurse who worked in an ER in the Bronx and was able to write poetry about what happened in the intensive care unit when we had the writing workshops,” Hirsch said. “In the first workshops we had 20 or 30 people. We started out with people really far away from each other looking at their phones. Three or four hours later we had told each other some really intimate things and we were in this big huddle.”

The experience was moving to the organizers, but also touching and gratifying for the participants, including Galván, who said: “It became such a community of sharing and seeing the devastation of this event in our lives, but also trying to find a way to improve the situation moving forward.”

In addition to building community among its participants, the project allowed local artists to exhibit their work, and provided people with opportunities to share their stories. A map on the project’s website allows visitors to hear recordings of individual stories.

“It’s a way to give an account of the reality of what happened. Each individual has such a big story and to see individuals say they had to stop going to school, they couldn’t go out, they didn’t have anything to eat … It has been a very traumatizing experience for our community,” Galván said.

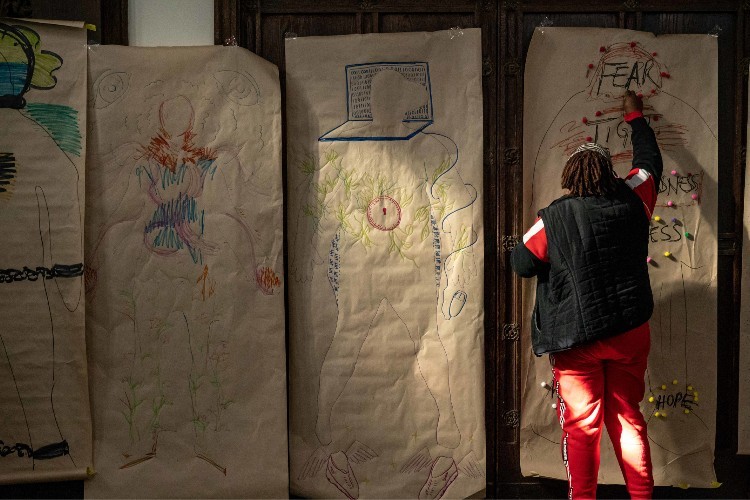

In April of 2022, the Imagine Repair exhibition at St. John the Divine provided an opportunity for participants to display their works, as well as for performances and conversations about the project. Some of the works exhibited were from Aquí/Here, where participants reflected on their individual and collective experiences by mapping them onto outlines of their bodies and maps of New York City. The workshop, according to Galván, helped participants bring out and share private feelings and suffering they were experiencing.

What’s Next for the Project

The organizers of the Zip Code Memory Project have goals that go beyond just helping New Yorkers express their experiences.

“Our aim was to build on the range of creativity that people have and develop some sense of what a more just system might be like, and how to build justice and repair on the basis of loss,” Hirsch said.

This is echoed by participants, including Galván, who said: “We have to make a big effort to bring about changes. I hope that this documentation makes sure that that is up front. Do not allow people to forget it.”

The Imagine Repair exhibition wrapped up in May, but the Zip Code Memory Project isn’t finished. They’re training more people in the techniques used in their workshops and having deeper conversations to tackle complex political issues.

Keep Up with the Zip Code Memory Project

They have created a short film, Together, Not Alone, directed by Gabriella Canal and Judith Helfand, which will be screened in the fall. They are also planning more screenings and discussions, including one with artists who will discuss the possibilities for a New York City COVID memorial.

“We want to pause and acknowledge the losses,” Hirsch said. “And have the larger conversation about commemorating COVID that acknowledges the enormity and intimacy of loss, while also fighting against inequality and for social justice.”

The Zip Code Memory Project was supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, the Center for the Study of Social Difference, Columbia School of the Arts, the Society of Fellows/Heyman Center for the Humanities, and the Institute for Religion and Public Life, as well as numerous community partners and other universities, including CCNY, NYU, and Yale. To learn more about the project, visit their website or follow them on Twitter or Instagram.