5 Things to Know About the Life and Times of Uptown Trailblazer Yuri Kochiyama

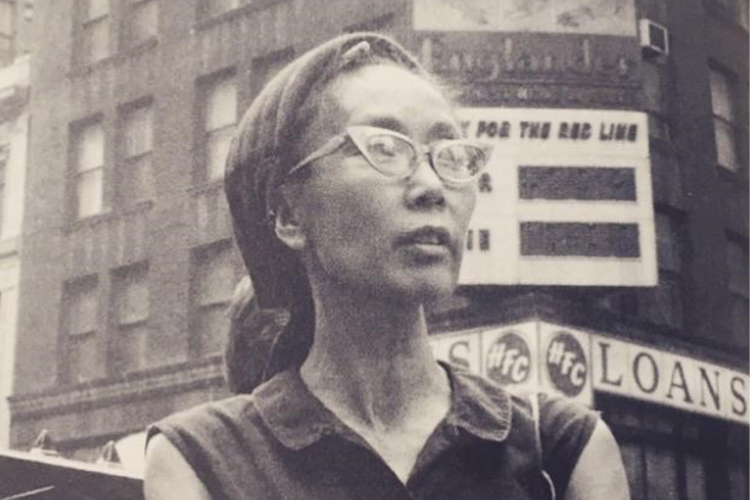

The pioneering activist—who once called West Harlem home—contributed to the advancement of social justice.

Harlem has served as the backdrop for social, political, and cultural movements across generations. The historic Upper Manhattan neighborhood has also been home to changemakers who have instrumentally advanced social justice. Among them is California-born, Japanese American civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014)—a former Manhattanville Houses resident—who tirelessly fought for human rights and dedicated her life to amplifying the voices of marginalized communities.

"Remember that consciousness is power," she shared during one of her riveting speeches. "Consciousness is education and knowledge. Consciousness is becoming aware. It is the perfect vehicle for students. Consciousness-raising is pertinent for power, and be sure that power will not be abusively used, but used for building trust and goodwill domestically and internationally. Tomorrow's world is yours to build."

In honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Columbia Neighbors is celebrating Kochiyama’s pivotal contributions and uplifting her story. Here are five things you should know about the unsung activist’s life and legacy.

Kochiyama’s passion for social justice stemmed from a harrowing coming of age experience.

Lived experiences often serve as catalysts for purpose, and this rang true for Kochiyama. Following the devastation of the Pearl Harbor attacks in 1941—which launched the United States into World War II—the activist and her family were forcibly sent to incarceration sites under Executive Order 9066. Kochiyama and her loved ones spent two years confined in an internment camp in Arkansas; living in decrepit and inhumane conditions. Her father Seiichi Nakahara—a first-generation Japanese American—was arrested along with others of Asian descent by the FBI after being deemed “national threats.” Nakahara’s health declined while in custody and upon his release, he passed away.

“Everything changed for me on the day Pearl Harbor was bombed," she told the San Francisco Bay View. "On that very day, December 7, the FBI came and took my father. He had just come home from the hospital the day before. For several days we didn’t know where they had taken him. Then we found out that he was taken to the federal prison at Terminal Island. Overnight, things changed for us.”

For Kochiyama, the loss of her father and the direct exposure to these oppressive measures revealed ugly truths about racism in America. Later in life, during the late 1980s, she was at the forefront of the fight for restorative justice through reparations for the 120,000 Japanese Americans who were impacted by the racially motivated incarcerations of WWII. This definitive chapter of her life heavily influenced her path in activism.

Kochiyama was an influential supporter of local liberation movements.

After moving to New York City with her husband Bill Kochiyama—whom she was married to for 47 years—the couple lived in predominately Black and Brown New York City neighborhoods, which provided them with another lens into the systemic inequities faced by marginalized communities. In the 60s and 70s, Kochiyama became involved in liberation movements. She and Bill were a part of the Asian Americans for Action; a then New York City-based organization that had a mission rooted in spreading awareness about issues experienced by Asian Americans.

She became a member of the Young Lords’ Party—which formed in Chicago, but has a strong presence in East Harlem—and was part of the Statue of Liberty takeover, which was led by Puerto Rican nationalists in 1977. She worked closely with Black empowerment organizations to fight for reparations. Kochiyama also led efforts around criminal justice reform; advocating for the releases of Black Panther member Mumia Abu-Jamal as well as Marilyn Buck and Yu Kikamura.

She was friends with the late civil rights icon Malcolm X.

Kochiyama and Malcolm X’s friendship was built on the foundation of a shared vision for justice. She and her husband first met the civil rights leader in 1963 in Brooklyn. Malcolm X would often mail letters to the Kochiyamas during his global travels. When Malcolm X was tragically assassinated while delivering a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Washington Heights in 1965, Kochiyama—who was sitting in the audience with her teenage son Billy—immediately ran to his aide.

“I feel that Malcolm did more than anyone else to let me see what's really happening in the world and why,” she said in an interview. The two trailblazers also shared a birthday.

She called Manhattanville Houses in West Harlem home.

At the height of the civil rights movement, the Kochiyama family’s apartment in Manhattanville Houses became a haven for a collective of social justice activists who were on a mission to drive change locally, nationally, and globally. Her home was where the mobilization of movements took place and bridges were built among those fighting against the suppression of communities of color.

It was in her Manhattanville apartment where she hosted the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Study Mission. Cognizant of the cross-cultural struggles in the quest for justice, she connected Malcolm X with those who were impacted by the atomic bombings in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The apartment is also where she organized community-driven meetings, penned newsletters, and led planning around other human rights efforts. The Kochiyama family lived in Manhattanville Houses for nearly four decades.

A mural created in her honor lives in Harlem.

In celebration of Kochiyama’s legacy, a vibrant mural that depicts the activist and late civil rights leader Malcolm X, titled From Harlem with Love: A Mural for Yuri and Malcolm, was created on the corner of 125th and Old Broadway; just steps away from where she and her family lived. The artistic homage was spearheaded by Kochiyama's family and a collective of activists and artists who were inspired by the legacies and friendship of Kochiyama and Malcolm X.

“Even beyond 1999, she still maintained connections to the Manhattanville Houses community,” Julien Terrell—one of the volunteers behind the project—shared in a past interview. “She did a great deal of work out of her apartment; Malcolm met with a group of hibakushas (Japanese A-bomb survivors) there, and for years she would invite people from the community to her apartment to talk about issues. So, this location connects so many parts of her life.”